What is My Topic?

What’s roasting, little poulets? For this In-Depth project, I have decided to do group theory. Group theory is an incredibly important topic of study in the domain of abstract algebra and has been a major player in modern math (1800’s plus). Intuitively, it seeks to understand symmetry by creating a collection of actions on an object, and then studying what happens when you composite those actions. However, since this is abstract algebra, it turns out to be very fruitful to extend the rules of these symmetry groups into generalized rules, and that’s really where the good stuff is. But let’s not get caught up in the morass of abstraction. What is group theory? It’s math that studies symmetry.

Why Would You Do That?

There are a lot of merits to group theory that would reasonably get you interested on their own, but the main reason I chose this above all others is because of how applicable it is. Group theory has a strange number of applications. You’d never imagine something that sounds as esoteric as my description above would be as widespread and practical as it is. For example, groups are intuitively about symmetry, so it makes sense that they can help you solve Rubik’s Cubes. But what if you’re a chemist, and you want to analyze the emission spectrums of elements during a spectroscopy experiment? Group theory’s got you covered. Trying to disprove the existence of quintic equations? Have you ever heard of group theory? Or perhaps you’re a quantum or particle physicist, and you’re trying to understand the fundamental building blocks of the universe. Group theory’s a prerequisite. It’s something that ranges from conservation laws in physics, all the way to… geology (shudder). I shouldn’t need to explain how utterly baffling it is to hear about the central role group theory plays in all these disparate fields. This completely unexplained applicability activates some deeply innate curiosity that you, reader, must surely share in some capacity.

There is another, more practical, reason as well. Base group theory requires little mathematical background to understand. Aside from some basic familiarity with set notation (which can be easily gained), it’s a subject that stands very well on its own yet is so foundational to many other things. This is very appealing for any mathematically enterprising highschooler who frequently gets barred by layers of prerequisite foundational knowledge. However, this comes with a price, in that group theory is at its most interesting when applied, and that application requires the standard foundational knowledge of the chosen field.

Group theory is also helpful to what I want to do in the future considering their inseparable importance to quantum and particle physics. Not only that, but, according to my mentor, you don’t usually get a dedicated group theory course if you’re solely focusing on physics. With all of those reasons in mind, it seems like a good subject to explore for In-Depth.

Not to mention that some group theory things (like their connections to Noether’s conservation laws) are just cool. Why wouldn’t you want to learn about that?

Who Do I have Aiding Me?

For my mentor, I have reeled in a man named Russell who has a Ph. D in physics from the University of Cambridge. He picked up group theory while doing his studies thanks to its applicability in physics. Granted, it’s been a little while since he last used group theory, but he’s brushed up for this project.

What is the Plan?

The final product of this project is to create a lesson about a group theory topic. Either some theorem or interesting application that I learn about will be spun into a single video lecture written and recorded by me. More than just an encapsulation of what I learned, I want the people who watch it to genuinely learn something from it, which I’d say is one of the most thorough tests of knowledge I could ask for.

The first four months of the project will be focused on general lessons within some branch of group theory. What will probably happen is my mentor and I will find a book or lecture series about our topic and consume some constant portion of it every week. We will then meet up every week to discuss the contents of what we just ingested, while probably assigning homework problems along the way.

The last month of the project will be my time to focus on the lesson I make. Having hopefully picked a suitable topic to make my lecture on, the first two weeks will have a pair of more focused lessons. The last two weeks will be when I start writing and recording my lesson, checking in with my mentor sporadically through the process.

I will also post biweekly blog posts meant as a record of my learning. They should include my struggles and thoughts learning the subject and general reports on my progress.

What is the Challenge?

That already provides me quite a lot to do, but of course it’s not enough. The little cherry on top for this project is my challenge. By the end of the five months, I want to have self derived some non-trivial result in group theory. It doesn’t have to be original, as long as I had no help in the process and derived it completely independently. This isn’t too unrealistic, as I’ve already done stuff like this before, just not with a field as abstract as group theory. This challenge should also be easily scalable if its difficulty doesn’t match my ability. If it’s too easy, aim for more results. If it’s too hard, then that’s too bad. I also haven’t allotted any specific time frame to complete this challenge. I plan on doing it lightly for the first four months, and then to put more time aside in the last month. Should I manage to complete this challenge, the results will be shown in the video lecture I make.

What Have You Done So Far?

According to my mentor, I’ve already “basically” learned group theory, which is rather encouraging.

I didn’t realize how little there is to be found within basic group theory until the first meeting with my mentor last week. Given that I already know the standard definition of a group, I’m pretty much fully equipped to start digging into applications. And that’s where you learn most group theory: by applying it to something, otherwise you learn a lot of seemingly random stuff that doesn’t fit together at all.

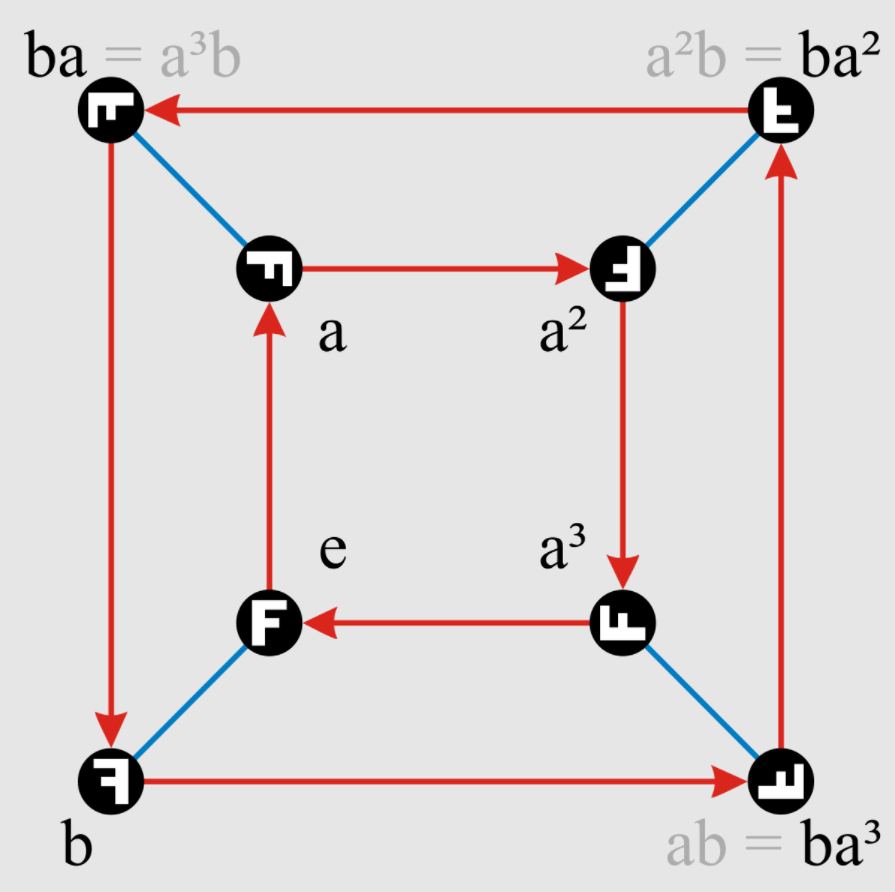

So, our first meeting largely consisted of discussing where we wanted to go, and that’s what I’ve been responsible for researching since. Currently, I’m mainly split between Noether’s conservation laws, group theory’s application to linear algebra, and the solvability of quintic equations. Chemical spectroscopy was also thrown around, but I’m not particularly interested. I’ve also watched some of Matthew Macauley’s “Visual Group Theory” (linked below) as a nice overall primer, and perhaps preparation for Galois Theory if that’s we decide to do.

Materials

Below is a list of the resources I currently have available to me that I will be using as aid and self study material.

Groups Around Us by Pavel Etingof

https://klein.mit.edu/~etingof/groups.pdf

Visual Group Theory by Matthew Macauley

https://youtu.be/UwTQdOop-nU

Adventures in Group Theory by David Joyner

https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/adventures-group-theory

Group Theory by J.S. Milne

https://www.jmilne.org/math/CourseNotes/GT.pdf

Group Theory for Chemists, Second Edition by Kieran Molloy (requires Burnaby Library account)

https://learning-oreilly-com.proxy.bpl.bc.ca/library/view/group-theory-for/9780857092403/xhtml/9780857092410_cover.htm

A Friendly Introduction to Group Theory by Jake Wellens

https://math.mit.edu/~jwellens/Group%20Theory%20Forum.pdf

MIT Open Courseware

https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/mathematics/18-703-modern-algebra-spring-2013/lecture-notes/

Classical Mechanics, Third Edition by Goldstein, Safko, and Poole (largely supplemental)

https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B5nvP_eIBydjYWMwMDhhY2QtNzBmOS00NGM5LWE3NWQtZjFiN2NlNTk3ZTNj/view?resourcekey=0-7x6BeBkfuEOr3-ARElwIBw

This quote is perhaps the most inspirational thing I’ve ever come across. Though it doesn’t pertain to group theory in particular, it largely encapsulates my approach to learning math.

“Ludwig Boltzmann, who spent much of his life studying statistical mechanics, died in 1906, by his own hand. Paul Ehrenfest, carrying on the work, died similarly in 1933. Now it is our turn to study statistical mechanics.”

-David Goodstein in States of Matter